GLAUCOMICS

AN INTERVIEW WITH MIRIAM WAITE ON DEVELOPING PATIENT EDUCATION COMICS

Introduction

Graphic medicine as a field is young, with the term itself only being coined in 2007 by UK physician-cartoonist Ian Williams (Green & Meyers, 2010), but there is a surprisingly long history of attempts to use comics in health education. This history includes, for example, uses in formal education, including medical education, community development, public health, and direct patient education (Czerwiec et al., 2015). Perhaps less surprising is that for much of this history, studies have been far from rigorous and primarily report on the “appreciation” of the comic by the target audience. In other words, we have decades of studies that tell us that people—of all ages and nationalities—enjoy comics and find them an approachable means by which to learn health information. What we do not know is, well, everything else. A scoping review meant to further illuminate this history is under way (Noe, Makowski, Levin, & Lund, 2017).

With the field of graphic medicine approaching its tenth annual conference in 2019 (see www.graphicmedicine.org for more details) and the emergence of medicina gráfica dedicated to Spanish-language applications of the field, we are seeing a surge in scholarly work dedicated to answering the questions the past does not provide. One such example comes from cartoonist Miriam Waite, who is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Dundee in ‘Serious Cartoons – Visual Communication of Personalised Health Information’. Over the course of a few months, Miriam and I spoke via email about her work, why comics for patient education, and the challenge of gaining acceptance with comics in medicine.

Throughout the interview, you will hear how Miriam came to the idea of using comics for health education and the challenges presented by working in a field with significant research gaps. You will also hear enthusiasm for the possibilities presented by graphic medicine that we hope inspires you to begin your own comics and medicine journey. If you find yourself so inspired and hope for further direction, please, seek us out!

Matthew: Graphic medicine is such an interdisciplinary field, so first, what is your background with both comics and medicine?

Miriam: Before the PhD I was the junior medical artist at the Royal Preston Hospital, where, among other duties, I would design information for patients. ‘Design’ is a bit of a strong word—I would really just drag and drop text into a template, maybe draw some pictures if I was allowed. Anyway, I began to see how woefully inadequate patient education materials were at communicating complex information and wanted to do something about it. In my Medical Art MSc I had dabbled in comics, and I saw their potential, but there was not much creative freedom in my hospital (anything not following the brand was shot down in flames by management). The PhD popped up at just the right time, as my contract was coming to an end.

Matthew: Have you been much of a comics reader in the past or is that recent as well?

Miriam: I was in a rut, after leaving university with a degree in archaeology and latin, not wanting to pursue a career in either... and my housemate met someone who was a medical artist, which sounded like fun. Because previously I had had a lot of enjoyment and success as a portrait painter and also in the illustration module of my archaeology course, and I was also a science nerd, I thought that medical illustration sounded like a fulfilling idea. So really, I just happened to stumble upon a way to draw things that had the potential to benefit society, and interest me!

Comics was even more happenstance. There was a module on my medical art masters called ‘Communication to the public’, and I wanted to make an animation for it. My sister had recently had an asthma diagnosis so I asked what info she’d find beneficial, and made a storyboard with her suggestions. Time constraints meant I was never going to finish an animation in time, so I turned it into a comic! This comic got seen by some people at the local dentistry school, who commissioned some paediatric dentistry comics.

Once I was in my medical artist job at the hospital, I forgot about comics a bit. I was making these leaflets though which I thought dreadful. I had no power to make them more visually interesting, or to make the test more understandable and engaging... but I desperately wanted to. And when my dad was booked in for his heart bypass surgery he was given this 52-page ‘leaflet’ of which he read only one paragraph (the bit about going on holiday) because the leaflet was just so dense, boring and scary. I hated the idea that someone who didn’t have a willing family member to trawl through it for them was going to miss some of the vital information.

Matthew: Your experience with patient education materials matches the scholarly literature for sure. Can you tell us a little more about the specifics of your PhD? Particularly how glaucoma came to be your focus?

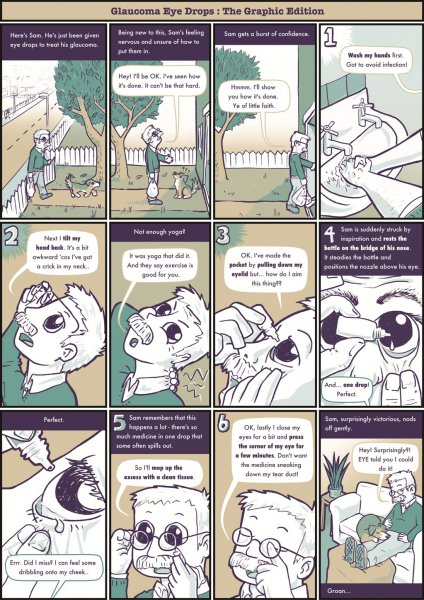

Miriam: So when I got offered this PhD (called ‘Serious cartoons: visual communication of complex medical information to patients’) I researched the possibilities of comics in greater detail than I had in my masters and concluded that they were my Holy Grail! There doesn’t seem to be too many drawbacks about them. I’m only really worried about whether patients will accept the medium and trust its contents. My hypothesis is: To what extent is it possible that comics can be made to provide all the information a patient with a chronic disease (e.g. glaucoma) needs about long term care of their condition?

In the PhD I came in contact with an ophthalmologist who wanted to improve her patient information. She was initially sceptical about the idea of comics for her patients (who are mostly in their 70s) but, after my comic received some very positive feedback, became an enthusiastic convert. This is really where the PhD began.

Now I’m halfway through my 3 year PhD, about to embark on my main study, qualitatively assessing comics’ potential patient education role for glaucoma patients. Fun!

|

|

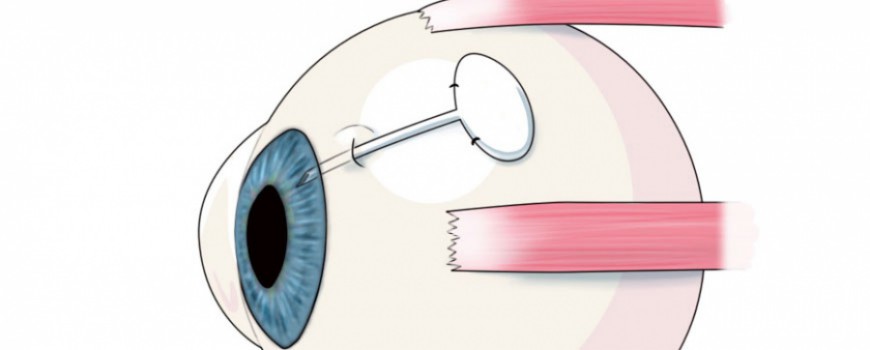

| The Silent Thief of Sight -a visual metaphor for the slow, imperceptible advancement of glaucoma. | Glaucoma Eye Drops - a graphic instruction guide on the instilling of eye drops. |

Matthew: So as a PhD candidate, you'll have to write a dissertation, correct? Do you think you'll tackle that in comics form, similar to Nick Sousanis' Unflattening or go a more traditional route?

Miriam: I’ll be writing my thesis in a mixture of essay and comics. I think that it would be hypocrisy to NOT write some of it as a comic, if I’m exploring the format’s powers of communicating complex information! There may be parts that it just makes more sense to write as an essay, but don’t worry, there’ll still be plenty of pictures.

Matthew: That sounds fascinating! Have you already discussed this plan with your advisor(s)? Are they supportive and open to it? I've not seen many visual dissertations, so I'd love to hear more about the logistics and process of making this happen.

Miriam: My supervisors think even half essay and half comic is not enough comic! These are the joys of PhDing at an art school. I suppose what makes me apprehensive about the idea of 'full-comic' is that, coming from a science background, I’ve been conditioned to work in a traditional structure and it’s hard to convince myself that it can be done otherwise. My intention then is to draw introductory comics that summarise their following chapters. In this way I can do what I want to do with patient education materials - give the reader the essential information in easy-to-digest comics segments, but also give them the opportunity to delve deeper with text. I like a bit of variety with my reading materials, and I hope my examiners will too!

Matthew: I first got to you know and you work via Twitter (@NoetheMatt and @MedComixPhD) — which is quite common in graphic medicine — and I noticed that you put together a comic explaining what a comic is. Can you tell us about why you felt you needed to, did it have to do with your concern about acceptance of the medium, and how you come to your definition?

Miriam: My comic on comics really came about through my need to establish a definition upon which to build my PhD. You see, there seemed to be a lot of disagreement in the literature—so much variation in what constitutes a comic—and I wanted something concrete for my project. It helps me to frame my comments on other research.

Matthew: That’s certainly true! I often call the definitional problem in comics the “3rd rail” — touch it at your own risk! How did you make your decision on what to include?

Miriam: I didn’t really include any groundbreaking details in my definition of comic. ‘Comics must have embedded text’, for instance, seems so obvious that it’s almost insulting to the reader to spell it out in the definition. But you see, I saw an article that contained a sequence of captioned illustrations, which the authors (and citing articles) called a comic. It was by most definitions a comic, but I just felt a little niggle about it. Don’t you think that a bit of the harmony between words and pictures (that’s kind of comics’ raison d’être) is lost when the words are spatially removed from the images? Anyway! I want to update my definitions a bit to define the different types of medical comics too. I’m never satisfied!

|

|

| "What is a comic", Part 1. | "What is a comic", Part 2. |

Matthew: You mentioned in our discussion that you’re writing now about how to “address the problem of how best to design medicine information comics”. Can you expand on that? What problems specifically come to mind?

Miriam: Well, I suppose, I would like to address my problems with designing medicine information comics! I don’t know about humour in medicine information comics. Should serious issues always be dealt with in a serious tone, or do people allow comics to be more personable than traditional formats? What about trust, will people just not trust information given in such an informal way? How does patient involvement change the design of medical comics?

Matthew: You were recently seeking participants for a focus group on making more engaging patient information, with the phrase “co-designed comics” coming up. Can you describe what that is?

Miriam: Well, I’m yet to iron out the finer details of what co-designed comics will be! Essentially, they’ll be comics designed in collaboration with multiple patients, involving them in every stage of the process. Right now, traditional patient education materials usually have very little input from patients. I’m hoping that the involvement of patients, the principle audience, right from the very start will help me understand better how to make effective comics.

Matthew: Can you describe a little more of that process? So, for example, what are the steps in developing an educational pamphlet and is the comic development process different?

Miriam: Before this PhD I had a bit of experience in the design process of NHS medical information in my hospital job. There, information leaflets would be written by medical professionals, okayed by a patient participation group (around 5-10 patients who meet regularly to discuss improvements to hospital services) then published. I think that a problem with this method is that okaying a leaflet is quite passive, and might not produce the most patient orientated information. At the moment my comics-making process is quite similar, but in my project I’m proposing that active involvement by patients right from the scripting stage could help make more engaging patient information and inform my later comics-making practice.

Matthew: As you’ve probably discovered in the first half of your PhD, there are some large gaps in the research on comics in medicine. How does your work fit in those gaps?

Miriam: As you’ve said, the gaps are huge. I’m really going to have to wait to see where it all fits, from what I find out with my discussions with patients. I realise this is a very unsatisfactory, non-committal response!

Matthew: Fair enough! Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Miriam: Just my excitement about how the project will progress! Thanks Matthew for your excellent interviewing (particularly in the face of my vague responses!) and Tebeosfera for their interest in graphic medicine.

References

Czerwiec, M.K., Williams, I., Squier, S., Green, M., Myers, K., & Smith, S. (2015): Graphic Medicine Manifesto. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Green, M. & Myers, K. (2010): “Graphic medicine: Use of comics in medical education and patient care”. British Medical Journal, 340(7746), 574-577.

Noe, M. N., Maowski, S., Levin, L. & Lund, L. (2017): “The Use and Efficacy of Comics in Healthcare: A Scoping Review in Graphic Medicine”. National Network of Libraries of Medicine New England Region (NNLM NER) Repository. 46. https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/ner/46 .